Warra-Warra-Wai not a welcome but a war cry

Bruce Stannard continues his 250th anniversary tribute to Lieutenant James Cook, Commander of HM Bark Endeavour, with an account of his historic voyage northbound on the eastern coast of New Holland.

“History is facts that in the end become lies;

Legends are lies which in the end become History.”

Jean Cocteau

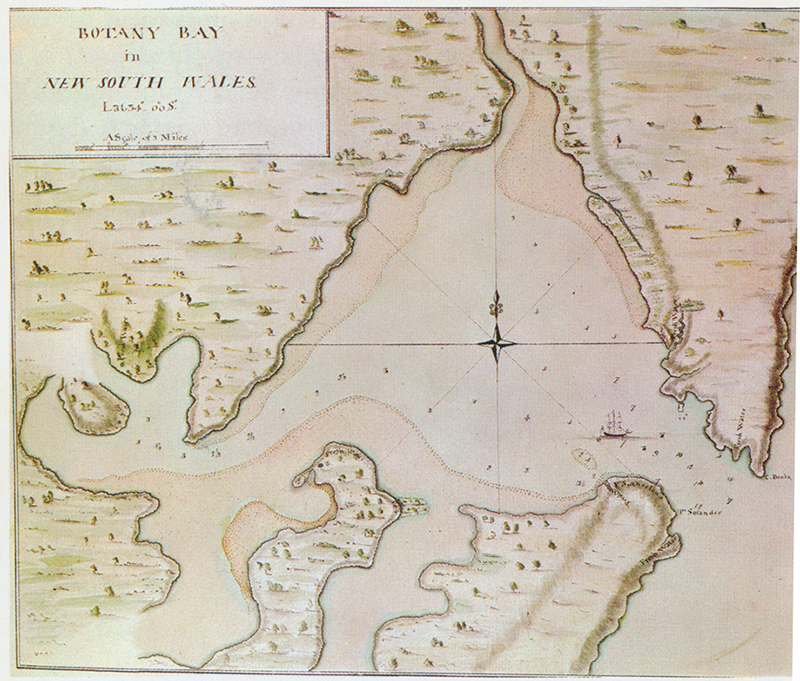

Botany Bay might today seem like a poor choice for an anchorage but after so long at sea one can well understand how even that shallow, exposed waterway might seem attractive, especially for the naturalists Joseph Banks and Dr Daniel Solander who were so keen to land on this hitherto unexplored coast. They went ashore on April 29, 1770 and in six days of botanising discovered a cornucopia of 132 plant specimens previously unknown to science. While the botanists were busy, Cook went about his business as usual, making a finely detailed chart of the broad bay he first named Sting-Rays Harbour and later, upon reflection changed to the far more appropriate Botany Bay.

Cook, who witnessed the devastating impact that European occupation had on the native peoples of North America, made repeated efforts to establish peaceful relations with the Indigenous inhabitants of New Holland. All the Endeavour journals record the way in which those overtures were either ignored or spurned with spears and shouts of “Warra Warra, Wai” – a war cry, not a welcome. But Cook was not about to go away. He landed, left gifts of trinkets, cloth and ribbons within the bark huts and took 40 or 50 of the 15ft bone-pronged fish gigs he found there. The British Museum still has those spears within its collection. English Colours were flown ashore throughout Endeavour’s stay in Botany Bay and an inscription carved on the trunk of a eucalypt with the name of the king, the ship’s name, month and year.

Cook spent only one day to “sound and explore the Bay” but this resulted in a beautifully detailed chart. His journal tells us he made “a little excursion along the sea coast” and explored the northern head of the bay in the pinnace. Although there are some who would have us believe that Cook followed Aboriginal tracks along the ridgelines to gain a glimpse of Sydney Harbour, there is absolutely no evidence, hard or otherwise, to lend any credence to this speculation.

Well aware of the tired state of his ship, Cook was anxious to press on with his running survey of the coast. On May 6, a light nor’westerly allowed them to weigh and come to sail. The boats were hoisted in and Endeavour ghosted out of the bay in a gentle breeze that gave Cook the offing he wanted. When the breeze went round to the south, he wrote it was “as if a benediction had been laid upon us”. Standing about two miles off the coast, Endeavour steered north by north-east with all glasses focused on the honey coloured sandstone cliffs off the larboard beam.

Endeavour was then logging about five knots and one can well imagine Cook briskly climbing, as he often did, the 40ft or so up the larboard ratlines to the Main Top, a platform just above the futtock shrouds, to closely observe the coast through his telescope. When the bark was just north of Bondi he would have seen inner North Head and 4.5 miles further on, North Head and South Head revealing the harbour entrance. His journal records only the most basic detail: that when Endeavour was just six miles north of Botany Bay she was abreast of “a bay or harbour wherein there appeared to be safe anchorage”.

Cook would have known at once that this great natural harbour facing the Pacific was potentially a place of enormous strategic importance to Britain, which is why he named it Port Jackson, after his friend and patron George (later Sir George) Jackson, Judge Advocate of the Fleet. The Harbour’s Heads stand almost exactly one mile apart and although North Harbour and Middle Harbour were hidden from his view, Cook would have plenty of time for careful observation of some of the bays and islands within the main harbour. It was a truly extraordinary discovery.

But he was not about to place any of that sensitive detail on his running chart, a document which would inevitably be published and find its way into French hands. Instead, he would no doubt have kept all that information in the strictest confidence, to be divulged eventually in his face-to-face debriefing with the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

There is evidence that Governor Arthur Phillip did have access to Cook’s closely guarded details of Port Jackson before his departure from England in command of the First Fleet. He divulged his knowledge of the harbour’s bays and islands on the eve of his departure and, as usual, the London Gazette, published its account the following day. So much for the need for secrecy!

Bear in mind that Phillip no sooner brought the 11 ships of the First Fleet to anchor in Botany Bay in January 1788 than he and his senior officers went north in three small boats to examine Port Jackson. When they returned to Botany Bay, they were astonished to find two French ships, L’Astrolabe and La Boussole commanded by the Comte de la Perouse, standing off and on under the pure white flag of imperial France. Although at that moment the old Anglo-French paranoia must have been running high, Phillip sent Captain John Hunter, commander of the armed tender HMS Sirius, off in a boat to greet the French with professional courtesy and to help pilot their ships safely into the bay. At the same time Phillip ordered the entire First Fleet to up-anchor and make an immediate departure for Port Jackson, which Phillip judged to be “one of the finest harbours in the world. One in which a thousand sail of the line might ride in perfect security.”

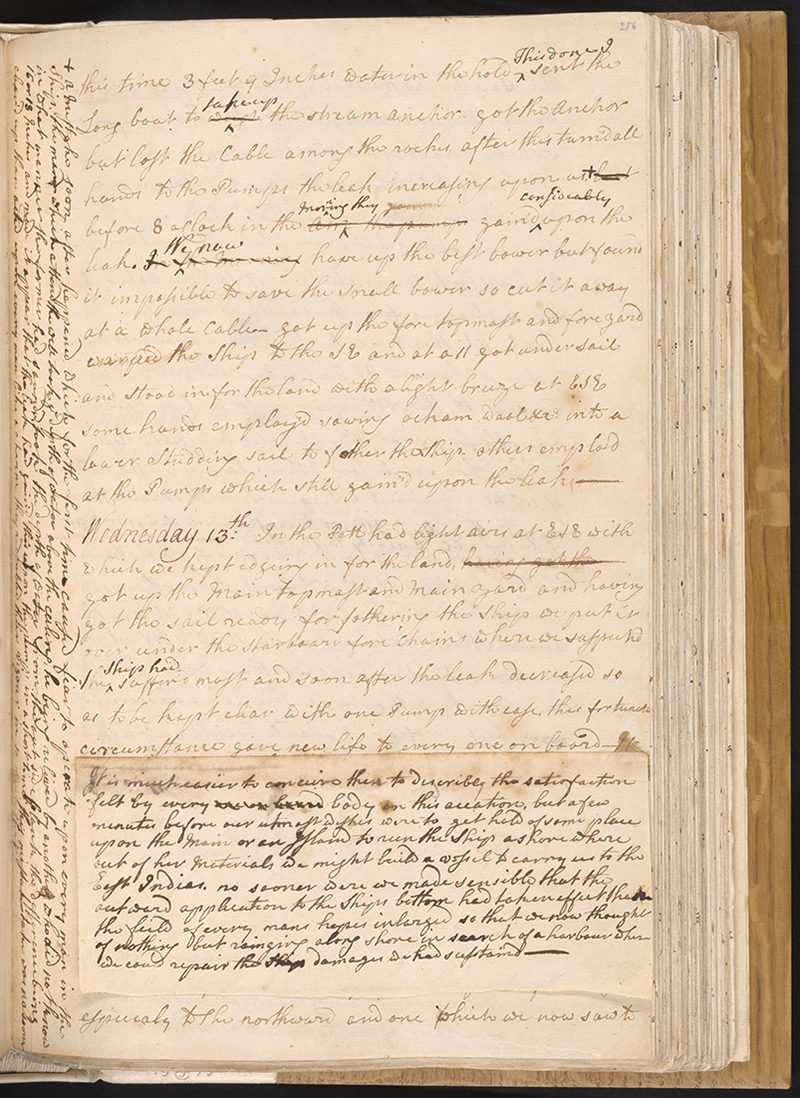

Endeavour steered north with Cook carefully surveying the coast while his wife Elizabeth‘s teenage cousin, Isaac Smith, drew the beautiful chart of “New Wales” which was at journey’s end to be renamed New South Wales. Cook took the opportunity to bestow prominent British names upon the ancient continent’s most conspicuous coastal features. On and on she sailed, gradually and imperceptibly becoming funnelled within the Great Barrier Reef, the “insane labyrinth” of 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands that stretches for over 348,000 square kilometres in the Coral Sea. On June 11, 1770, on a clear, moonlit night, with smooth seas and good visibility, Cook sighted his first coral shoals. Erratic soundings of 12 fathoms, 10, 8 and then 21 prompted his decision to steal along under double-reefed topsails. Just before 11 o’clock the leadsman’s reassuring call of 17 fathoms was followed by a loud bang. Endeavour came to a sudden, jarring halt. She was hard aground on a coral pinnacle at high water. All the journals tell us there was “no panic, no shouting, no alarm, no grumbling, no hurry or confusion – not even an oath”. This was due, in no small measure to the example set by Cook, who came on deck in his nightshirt and with his usual calm authority immediately gave orders to clew up all sails and hoist out the boats to sound around the bark and inspect the damage.

The boats carried out five anchors and used the capstan and windlass to hove them taut, but still she would not budge. They had struck at the peak of the spring tide and now with the ebb in full flow, Endeavour “began beating so violently upon the reef that those on the quarterdeck could scarcely retain their footing”. Cook ordered the ship’s top-hamper to be struck down on deck to reduce windage. In an attempt to lighten the ship some 30 tons of fresh water were thrown overboard together with six great guns, oil jars, condemned stores, stone and iron ballast and even firewood. A severe leak was discovered forward on the starboard side. Only three of the four elm-tree pumps were working – the fourth being choked with muck in the bilge. All hands, including the captain, Banks and the gentlemen, took 15-minute turns in pumping. They were not gaining on the leak and by now it must have occurred to some on board that if Endeavour did go down out there, six or seven leagues (20 miles) from the land, there would be nowhere near enough room in the boats for everyone to be saved. And yet, remarkably, all hands remained cheerful.

Bruce Stannard continues his tribute to Lieutenant James Cook in the next issue.

Main photo: Captain Cook’s Landing at Botany Bay, as portrayed by E. Phillips Fox in 1902.