The long-distance Pup

David Salter recalls two epic voyages made at a time when locally made one-pot engines powered our leisure boating

The 1920s and ’30s were the great decades of record-breaking in Australia. Kingsford-Smith in the air, Hubert Opperman on bicycles, Don Bradman on the cricket field. Record-breaking was a public mania, fuelled by breathless radio coverage and an excitable press with endless column inches to fill.

Many ventures were little more than publicity-seeking stunts. Others were such extreme tests of human endurance that they bordered on the outright sadistic and irresponsible.

Things were somewhat quieter on the water, although plenty of reckless dare-devils were happy to risk their necks trying to break speed records in ridiculously over-powered and flimsy craft. Solo long-distance voyaging was another obsession –daydreams of heroic feats of seamanship for ordinary recreational sailors.

But the essence of modest boating until the late 1950s was the 16-foot open skiff powered by a simple, single-cylinder petrol engine – the ubiquitous, unpretentious ‘putt-putt’. A million childhood memories were kindled by the intermingled, intoxicating smells of petrol, oil, bilge water and old fish heads, accompanied by that slow, comforting rhythm of a trusty one-pot ‘donk’.

But the essence of modest boating until the late 1950s was the 16-foot open skiff powered by a simple, single-cylinder petrol engine – the ubiquitous, unpretentious ‘putt-putt’. A million childhood memories were kindled by the intermingled, intoxicating smells of petrol, oil, bilge water and old fish heads, accompanied by that slow, comforting rhythm of a trusty one-pot ‘donk’.

The equivalent combination today would be the basic tinnie or runabout on a trailer with a 35hp imported outboard on the back. Efficient, but with none of the romance or history of a traditional Australian ‘putt-putt’. Compared to timber, aluminium and fibreglass are soul-less boatbuilding materials. Nor can a whining, high-revving outboard motor ever match the steady, plodding dependability of a traditional little combustion engine.

What may seem remarkable to us today is that the vast majority of those old engines were designed and made locally. At a time when Australia could still claim to be a genuine manufacturing nation, boating enthusiasts took pride in knowing that their ‘putt-putt’ power was home grown.

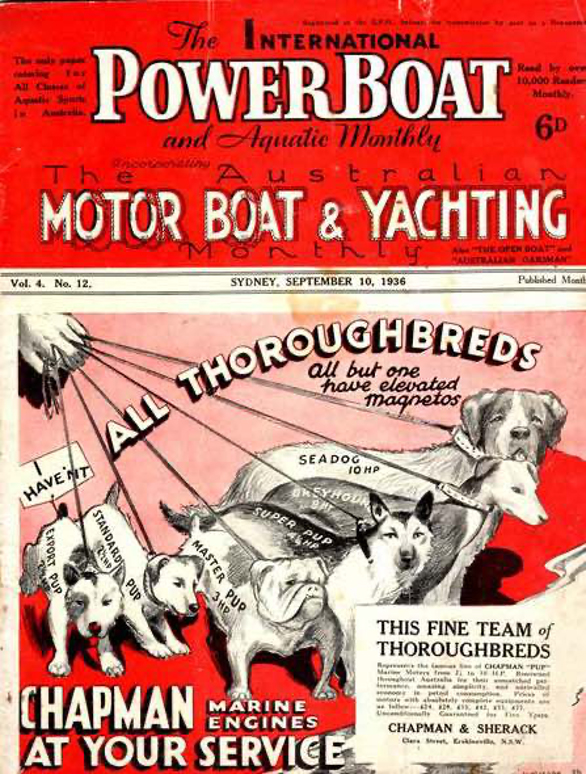

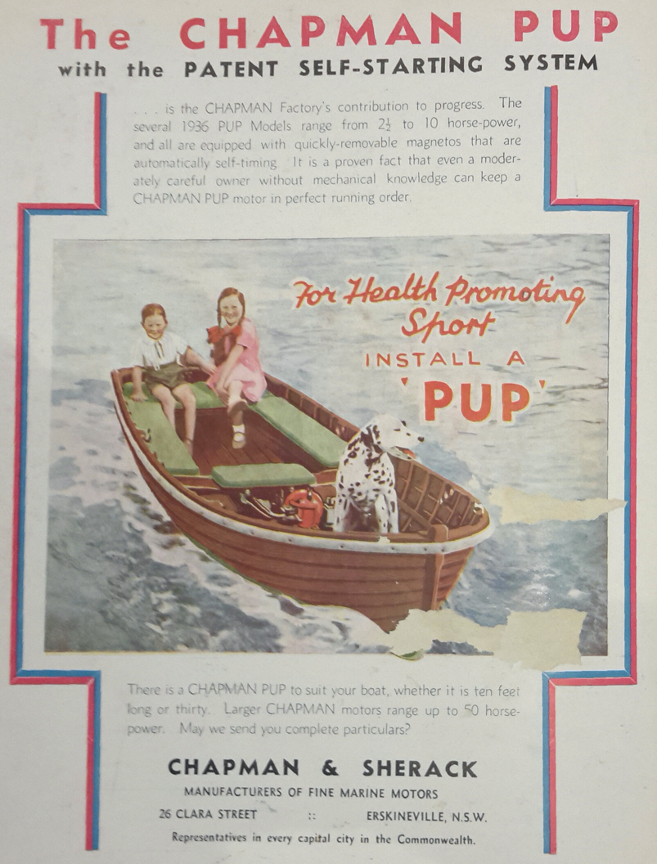

The most prominent brand names in the local marine motor industry 80 years ago were Chapman and Blaxland. The Chapman company (later Chapman & Sherack), had real entrepreneurial flair and dominated the market. They’d begun making marine engines in 1908 and came to real prominence in the 1920s when Michael Chapman patented an improved model that was marketed as the Chapman ‘Pup’. Their aggressive advertising leaned heavily on some rather tortured canine references, but a legend was born.

The most prominent brand names in the local marine motor industry 80 years ago were Chapman and Blaxland. The Chapman company (later Chapman & Sherack), had real entrepreneurial flair and dominated the market. They’d begun making marine engines in 1908 and came to real prominence in the 1920s when Michael Chapman patented an improved model that was marketed as the Chapman ‘Pup’. Their aggressive advertising leaned heavily on some rather tortured canine references, but a legend was born.

The appeal of the ‘Pup’ engines (and their imitators) was that they were simple, reliable and cheap to run. There were no electrics. The spark was provided by a magneto and the engines could be started by just spinning the flywheel with a crank or leather strap. Low revolutions delivered reasonable speed from modest fuel consumption. Back then, fishermen were in no great hurry to arrive at their favourite spot, and pleasure jaunts with the family were relaxed, all-day affairs. The ‘Pup’ suited those times to a tee.

Michael Chapman’s engines were so popular he had difficulty keeping up with demand. The factory at Erskineville in Sydney covered 10,000 square feet and produced a range of engines from the workhorse little 2½hp petrol motor up to 50hp diesels. The company also built launches from 12 to 30 feet in length.

Chapman’s upbeat promotional material emphasised the advantages of their self-timing magnetos, which were removable. (As the majority of these engines were installed in open boats, the easiest way for the owner to prevent theft was to simply take off the ‘maggie’ and pop it in his bag at the end of the day’s outing.)

An advertisement in the 1936 edition of The Australian Boating Annual boasted that “it is a proven fact that even a moderately careful owner without mechanical knowledge can keep a Chapman Pup motor in perfect running order.” That claim might seem far-fetched today, but 80 years ago the company had convincing proof that their little marine engines were truly reliable.

In 1935, Gordon Doherty, a young adventurer and journalist who’d already made a solo canoe journey down the Murray to Adelaide, determined to undertake a similar trip by sea from Sydney to Tasmania. When the Chapman company learned of his proposed venture they spotted a ‘record breaking’ promotional opportunity. They offered him the use of a clinker 16-foot motor launch with an extended low coach-house and 2½hp petrol engine. The boat was planked in Queensland kauri on spotted gum ribs and stringers.

Not surprisingly, the boat was named Pup, and Doherty was delighted to take sole command.

He soon completed an incredible voyage via Narooma, Lakes Entrance, Wilsons Promontory, Deal Island, Flinders Island, Lady Baron and finally down the Tasmanian coast to Hobart. Despite two full immersions the little engine apparently didn’t miss a beat.

The lone voyager then pushed on South and up the West coast to Macquarie Harbour. After a few days’ rest at Strahan he readied to continue his journey. But on the evening of Sunday 6 October, the day before departure, Doherty decided to take some friends he’d made at the little town out for a short ‘farewell’ pleasure cruise.

As Pup turned for home, some of the guests stupidly chose to stand on the cabin roof, capsizing the boat. Despite being no more than 50 yards from the wharf at Strahan, Doherty and two of his passengers drowned. After surviving more than 1,000 miles of open ocean, the intrepid young adventurer had perished in calm water.

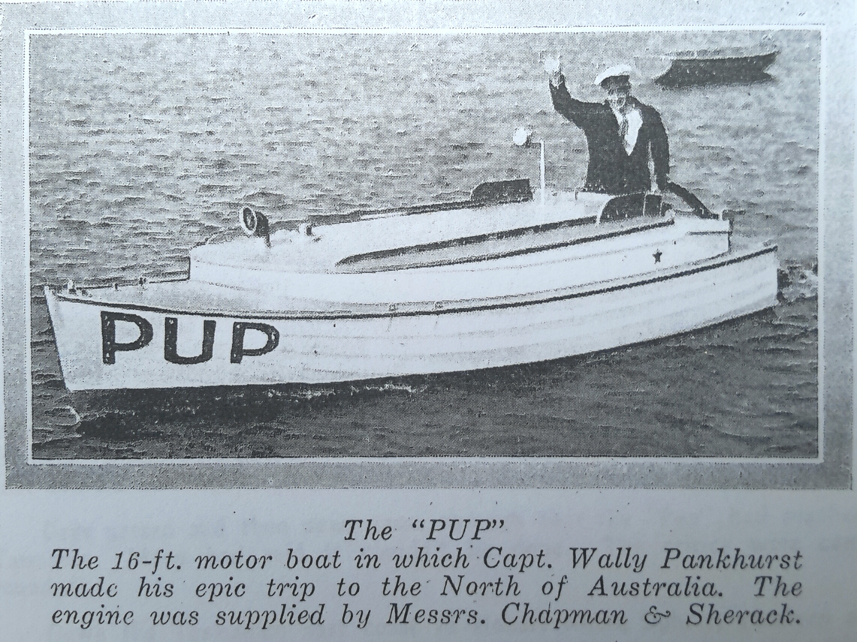

But that was not the end of Pup. The boat was brought back to Sydney on a coastal steamer to be hauled out on the beach at Watsons Bay. And there, by a remarkable coincidence just a year later, it was noticed by another intending offshore adventurer, Captain Walter Pankhurst.

Wally Pankhurst had first gone to sea in 1903, aged 11, as cabin boy in the three-masted barque Condor. Within months he’d been promoted to ‘junior seaman’, part of the working crew. After 10 years criss-crossing the world’s oceans he qualified as a First Officer and eventually captained steamers for the Wilson Line. After service in the Great War with the AIF Pankhurst returned to Australia, swallowed the anchor, and drove buses and taxis in Sydney.

But the love of the sea never left him. He’d been promising himself a voyage North up the coast, possibly as far as New Guinea. Pup seemed the ideal craft, and after a 15-mile trial off Sydney Heads he arranged to charter the tiny boat from Chapmans, who were again attracted by the promotional potential of the trip.

Pankhurst’s voyage was long, careful, and had a happier ending than poor Doherty’s trip to Tasmania.

His stop-overs included many of the safe harbours and anchorages well known to those who still cruise the Australian coast: Broken Bay, Newcastle, Port Stephens, Port Macquarie, Coffs Harbour, Byron Bay, Tweed Heads, Southport, Brisbane, Bribie Island, Mooloolaba, Noosa Heads, Bundaberg, Gladstone, Yeppoon, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville, Innisfail, Cairns, Cooktown, and finally an epic 500-mile leg to Thursday Island that took 11 days (and five stops) to complete.

Wally was a skilled seaman, but he also enjoyed good luck throughout the voyage. There was a near collision with a sugar lighter in sea fog south of Cairns, and off Noosa Heads he tangled with some tough patches of seaweed that damaged the prop shaft forcing him to beach the Pup for two days and effect repairs.

The trip took five months and ten days, and Pankhurst visited more than 50 ports along the way. But the adventure exhausted Wally and he was admitted to hospital on Thursday Island complaining of severe stomach pain. A telegram from the hospital to the Chapman company on November 10, 1936 rounds out the saga:

“Captain Pankhurst has arrived safely at Thursday Island but has been admitted to hospital. He is still under observation and the opinion is that he is suffering from very painful trouble in the kidneys, but otherwise he is physically fit.”

The Pup, in somewhat better health, was returned to Sydney as deck cargo on the SS Marella.

Today, original Chapman and Blaxland engines are prized collectables and enthusiasts scour the internet searching for obscure spare parts. The Chapman & Sherack factory at Erskineville was demolished in the 1980s. The site is now occupied by a rather shabby block of home units.