Providential Channel

How Endeavour survived the great coral labyrinth

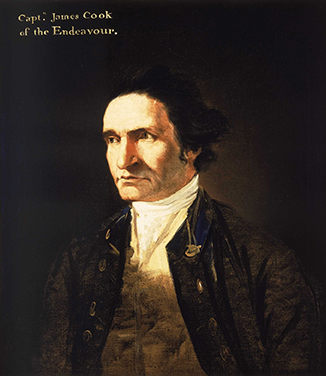

Bruce Stannard concludes his 250th anniversary tribute to Lieutenant James Cook, Commander of the Endeavour Bark.

Cook ordered Endeavour’s coasting anchor and cable to be deployed beyond the bar so that at the first sign of a favourable land breeze, the bark could be warped out of the river that now bore its name. On August 4, 1770, she crossed the bar in this fashion and with the aid of a light breeze coasted north.

It was to be a passage fraught with the greatest danger. Endeavour was constantly brought up sharply by seething coral shoals. She anchored time and again, veering out 1,500 feet of cable to cling to a tenuous hold in the teeth of relentless south-easterly gales and “prodigious great seas”. These boisterous conditions often required striking down the topgallant masts, yards and topmasts to reduce windage. Cook regularly climbed to the masthead, a lofty perch from which he tried to somehow divine the way ahead through what often looked like an impenetrable labyrinth. In day after day of high drama Cook’s consummate seamanship kept everyone’s spirits up. In the hands of any other commander, Endeavour almost certainly would have been lost.

When the wind moderated on August 11, Cook stood in for the land hoping to find a passage alongshore. Having steered between three high islands they flattered themselves that they were now clear of all danger with the open sea before them. But this was not the case. Thus, Cook named the prominent headland Cape Flattery. On August 12, Cook and Banks and a few men took the pinnace and with some provisions, set out for one of the islands. The only living creatures they found upon it were lizards, so Cook named it Lizard Island.

The island had a remarkable landform, a 1,000ft hill from whose summit the party looked down on what appeared to be an unending reef of rocks upon which the sea broke. This led Cook to suppose the rocks were the outermost edge of the reef. He and Banks slept that night under a bush on the beach and at dawn the following day he sent the pinnace out to sound the depths in a likely looking channel. Such a prodigious swell rolled in through this passage that the leadsman was unable to find the bottom. Cook took this as clear evidence of a safe passage and was so pleased with the discovery that he gave it the name: Cook’s Passage. Endeavour sailed through to safety in the open sea where the leadsman reported no bottom with his 140-fathom line. Ironically this was not where Cook’s orders told him he should be. The Admiralty expected him to chart the entire eastern coast of New Holland and so, duty bound, August 15 he turned back and steered due west toward the almost fatal shore. As they did so the breeze faded and left Endeavour wallowing.

On August 16 at four in the morning, all on board could clearly hear the roar of breakers pounding the reef just under Endeavour’s lee bow. The yawl was immediately lowered and sent ahead to try to tow the bark clear. But no amount of effort from the oarsmen appeared to overcome the tremendous force of the seas. Of all the dangers Endeavour had encountered, this was by far the worst. Everyone on board must have realised that if she were to be dashed to pieces on this coral wall rising sheer from the seabed, then all must perish. And yet even as they stared into the jaws of destruction, every man remained calm and attentive to the captain’s orders.

On August 16 at four in the morning, all on board could clearly hear the roar of breakers pounding the reef just under Endeavour’s lee bow. The yawl was immediately lowered and sent ahead to try to tow the bark clear. But no amount of effort from the oarsmen appeared to overcome the tremendous force of the seas. Of all the dangers Endeavour had encountered, this was by far the worst. Everyone on board must have realised that if she were to be dashed to pieces on this coral wall rising sheer from the seabed, then all must perish. And yet even as they stared into the jaws of destruction, every man remained calm and attentive to the captain’s orders.

The pinnace “much eaten by the teredo worm” was still under repair and could not immediately be launched. The ship’s carpenters hammered away furiously and, rough as their workmanship was, she was launched together with the longboat and yawl, and even Banks’ own dinghy. For extra leverage two large sweeps were deployed through the gunroom ports and these helped to bring Endeavour’s bow around.

As the ship’s foredeck bell tolled the fateful hour: six o’clock, Endeavour was no more than 80 yards from the breakers. The same high seas that washed the sides of the ship swept on to the reef so between the ship and destruction stood “only a dismal valley the breadth of one wave”. And yet, as Banks’ journal tells us “in this truly terrible situation not one man ceased to do his utmost and that with as much calmness as if no danger is near.”

At the critical moment, when all their efforts seemed too little, a tiny zephyr sprang up and with its assistance Endeavour slowly began to move away from the reef in a slanting direction. This slightest of winds wafted the ship about 200 yards from the reef and again fell calm so that all the old fears returned. By some miracle that Cook would later attribute to Providence, “our friendly little breeze revisits us and again draws us away.”

A small opening in the reef appeared before them and within it, smooth water. Although it was scarcely as wide as the length of the ship, Cook took resolve to push her in. But the ebb tide would not allow it, instead carrying the ship a quarter of a mile from the breakers. At last, under the influence of the towing boats she had an offing of about two miles.

On August 17 another opening was seen ahead and Lieutenant Hicks was sent to examine. He returned with a favourable account and Cook immediately decided the best chance of saving the ship was to sail through the channel to the sheltered waters within the reef. Although the channel was less than three quarters of a mile wide, Endeavour hurried through with the turbulent flood tide surging about the ship like a millrace. Once inside the reef they anchored in the perfect security of calm, clear water. Their deliverance, “which owed much to Divine Providence” caused Cook to name the passage Providential Channel.

On August 18, 1770, Endeavour got underway with a lookout at the masthead, a leadsman in the chains and the pinnace out ahead sounding. They were content to make barely two or three knots as they followed the coast to the very tip of the promontory named by Cook Cape York, in honour of the king’s brother, the late Duke of York. There, a very strong tide told Cook he had at last arrived at the long sought-for strait separating the eastern coast of New Holland and New Guinea. Cook gave it the name Endeavour Strait, in honour of the little bark that had borne them so bravely over those many miles.

Cook went ashore on a small, sandy island just west of Cape York and there with Banks, Solander and a small party of marines, stood on the crest of a hill where they could be observed from the ship. They raised the English Colours and the Marines fired three volleys which were answered by other Marines on the beach and still more from the ship. Seamen in the main shrouds gave three hearty cheers. In that brief ceremony Cook took possession of the entire eastern coast of New Holland for his Britannic Majesty, King George III.

In this 250th anniversary year, there are those of us who respect Lieutenant James Cook’s memory and acknowledge him for the great navigator, cartographer and seaman that he was. I believe we are fortunate having the world’s most famous explorer and discoverer at the beginning of our European history.

As for Endeavour, I regard her as Australia’s Flagship. Her very name lies at the heart of our national credo. Endeavour means “have a go” and that, surely, is a phrase every one of us can embrace.