Lieutenant James Cook and HM Bark Endeavour

Demolishing the myth of Terra Australis Incognita

Bruce Stannard continues his tribute to Lieutenant James Cook, Commander of the Endeavour Bark, in this the 250th anniversary of their history-making voyage.

The Endeavour’s first port of call after departing Plymouth was Funchal on the Portuguese island of Madeira. There Cook purchased a staggering 3032 gallons of wine, green vegetables, a live bullock and enough onions to issue 30 pounds to every man and boy on board. Although gimlet-eyed Admiralty accountants would later query the need for so many onions, they took no notice of all that wine. Cook was demonstrating his determination that this would be a healthy voyage, free from the debilitating scourge of scurvy. He was a taut but humane commander and although he had no hesitation in punishing those who disobeyed his orders, he also understood the psychology of seamen well enough to set his own example with officers and gentlemen in the Great Cabin all eating vitamin-rich sauerkraut (pickled cabbage). It wasn’t long before the Foremast Jacks sent a delegation to the quarterdeck asking for the same.

Bailed up in Rio

On November 13, 1768, Endeavour arrived in Rio de Janeiro where Cook hoped to procure further fresh food supplies and careen the bark prior to her passage into the Pacific. But there, despite Britain’s 50 years of peace with Portugal, Cook encountered implacable bureaucratic intransigence from the the Viceroy, His Excellency, Don Antonio Rolim de Moura, Conde de Azambuja.

Don Antonio, a wily old soldier, made it clear that he saw through the Admiralty’s charade. Endeavour, a plain little collier, could not possibly be a ship of the Royal Navy, he reasoned, let alone one on a scientific mission on behalf of the British king and the Royal Society. She must, he concluded, either be working as a merchantman-cum-smuggler or spy. It was a situation made all the more difficult by Cook’s determination to evade any mention of Endeavour’s secret missions in the Pacific. The Viceroy dug his heels in, insisting that no Englishman was to come ashore without his express permission.

Cook and Banks wrote indignant letters, but to no avail. With Endeavour lying at anchor under the Portuguese guns of Fort St. Sebastian, Cook was in no position to argue. Endeavour remained at anchor in Rio for three precious weeks while letters went back and forth. The lanky Banks, at 6ft 4ins or 193cm tall, was so frustrated that several times he climbed through a stern window at night and under the cover of darkness rowed ashore to obtain botanical specimens. Eventually Cook secured his supplies and completed essential work in cleaning and caulking the bark, repairing rigging and attending to minor repairs, ready for the next leg, the 2000-mile passage through squalls and contrary currents to the Strait of Le Maire.

Around The Horn

Endeavour made a spectacular entry into the Pacific when on January 31, 1769, she rounded the notorious Cape Horn. At 3am with a moderate breeze at ESE, Cook took the unprecedented decision to “set the studding sails” – the equivalent of flying modern-day spinnakers. In that reference, which would astonish later Cape Horn sailors, Cook records how Endeavour carried on with all her top-hamper. Not until the following afternoon did he see fit to strike the stun’sails and tuck a reef into his topsails. It was, he noted in his journal, “a circumstance that perhaps never happen’d before to any Ship in these seas so much dreaded for hard gales of wind.”

This was a bravura performance, but the always prudent Cook understood precisely how far he could push his little bark. He knew her intimately and had served his apprenticeship and become Master in identical vessels sailing out of Whitby. He was unstinting in his praise for her abilities and so were his officers and crew. Even the lubberly young botanist Joseph Banks, who suffered from sea sickness throughout the voyage, referred to the bark affectionately as “our little collier, Mrs Endeavour”.

Fort Venus, Tahiti

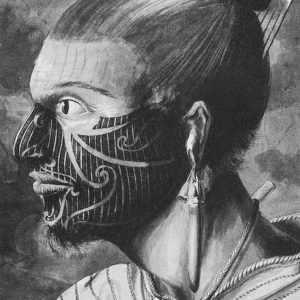

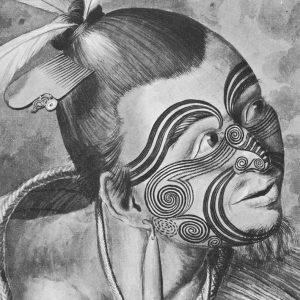

Endeavour had a top speed of only seven or eight knots but she was sea-kindly, untroubled by gales and only rarely shipped a green sea. On April 13, 1769, she came to anchor in the crystal clear waters of Tahiti’s Matavai Bay. There, Cook had plenty of time to establish good relations with the Tahitians and set up his telescopes within the protective palisades at Fort Venus, ready to observe the transit of the planet over the disk of the sun on June 3, 1769. Tahiti was, in Banks’ words “the purest picture of an Arcadia the imagination can form” and he made the most of it, botanising, and even stripping down to a traditional tapa loin cloth and dusting himself with ashes to join in Polynesian ceremonies. He made an effort to record and learn the language, and went as far as acquiring a traditional Tahitian tattoo on his right arm.

Cook was deeply impressed with the Tahitians. He praised their fine white teeth, their manly bearing, their attention to cleanliness and their open, affable and courteous behaviour to strangers. Although Cook made every effort to cultivate good relations and respect Tahitian culture, he allowed his crew to indulge their sexual appetites ashore where they paid for pleasure with iron nails. Needless to say, the armourer’s forge remained hot.

The Royal Society’s official astronomers, Charles Green and Cook himself, conducted their observations with the best of their instruments at Fort Venus, while as a precaution against inclement weather, additional observation stations were established on the adjacent island of Moorea and on an islet to the west. When the big day arrived, the weather was hot but perfectly clear. Cook wrote: “This day prov’d as favourable to our purpose as we could wish, not a Clowd was to be seen the whole day and the Air was perfectly clear, so that we had every advantage we could desire in Observing the whole of the passage of the Planet Venus over the Sun’s disk.”

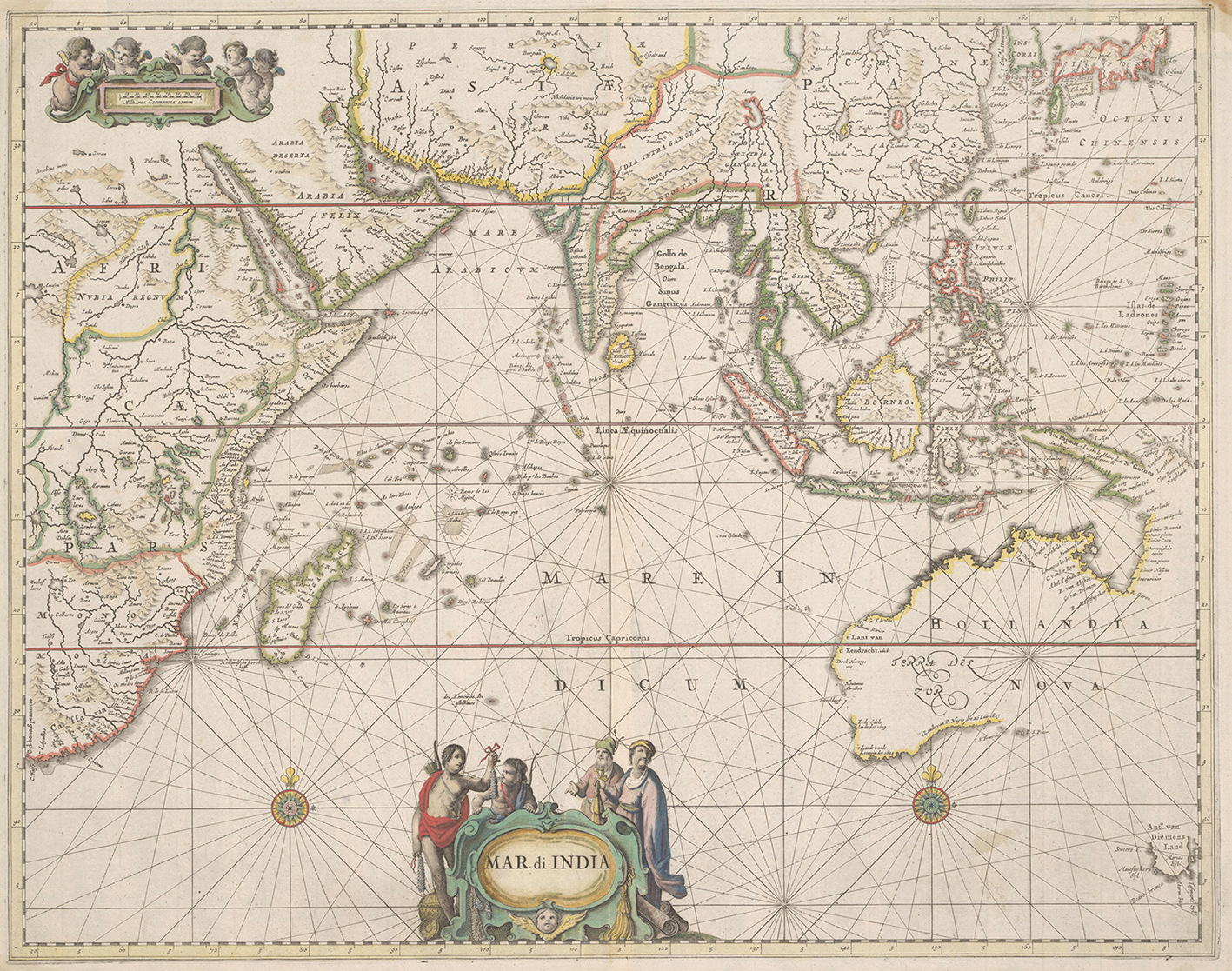

With his scientific work for the Royal Society at an end, Cook was free to leave the paradise after three months spent exploring and charting the islands while Banks continued his botanising. During his time, Cook was under the impression that Tahiti had seen no European visitors since the English Captain Samuel Wallis came upon the islands in 1767. When a Tahitian brought an iron tool to be sharpened, it became clear this was not the case. The tool was not of English design but Cook satisfied himself that it must have come from a Spanish ship sailing from the South American coast. If he had realised that it was in fact traded the previous year by the French explorer Bougainville, he might have acted with greater urgency as he opened his secret sealed orders. The Admiralty’s instructions for the second phase of Cook’s Pacific voyage ordered him “to make discovery of the Continent or land of great extent that there was reason to imagine existed,” searching to the westward between latitudes of 35 degrees and 40 degrees south “until you discover it or fall in with the eastern side of the land discovered by Tasman in 1642 and named by him New Zeeland”.

As Endeavour was being prepared for her departure, two Tahitians, Tupaia, a native priest from the main island, Raiatea, and his boy servant, Taiata, came aboard and asked to be taken to Britain. Banks, who agreed to pay for them both, wrote of Tupaia, “I do not know why I should not keep him as a curiosity as some of my neighbours do lions and tygers.” Tupaia would soon prove an invaluable guide, navigator and interpreter as Endeavour began to thread her way through the archipelago that Cook named the Society Islands “because they lay contiguous with each other”. Tupaia understood the intricacies of ancient Polynesian navigation, the so-called star paths. Although the deep sea swells told Cook and Tupaia that there was no possibility of a significant land mass ahead, there were to be many false alarms as Banks’ would-be continental landfalls proved to be no more than towering cloud banks.

On August 25, 1769, the first anniversary of their departure from England, Banks brought out a Cheshire cheese and tapped a keg of port so the gentlemen “liv’d like English men.” With the weather turning cold, others among the crew managed to surreptitiously tap into the bark’s spirit stores. John Reading, the drunken bosun’s mate, fell into an alcoholic coma and died after consuming three half-pints of rum, neat, which the bosun had given him “out of mere good humour”.

Young Nick wins a gallon of rum

On September 29, a seal was seen asleep on the surface of the sea and a barnacle-encrusted log was hauled aboard and scrutinised by the botanists. Both were taken as sure signs that land was not very far away. To encourage a sharp lookout, Cook offered a handsome prize – a gallon of rum and the promise to name the land for the first to sight it. At 2pm on October 7, 1769, that honour fell to the youngest member of the crew, when 12-year-old Nicholas Young at the mainmast head shouted “Land!” Young Nick’s Head on the eastern coast of New Zealand’s North Island, bears his name. As Endeavour drew closer and inland ranges appeared higher, the triumphant Banks and his “Continentalists” among the crew felt certain they were at last looking at the coast of the fabled southern continent. James Cook, the seamen’s seaman, begged to differ. He knew, as the Admiralty instructions stated, this was “the land discovered by Tasman and now called New Zeeland”. He then proceeded to give all the doubters a master class in surveying and chart-making, proving in the process that New Zealand was not one but two large islands. Cook’s charts were so accurate that they would safely guide mariners for the next century. Looking at them laid out in Endeavour’s Great Cabin, Banks and his supporters had to admit that he and Dalrymple and so many others had been utterly wrong about the existence of the unknown southern continent.

By far the most important aspect of Cook’s mission still lay ahead. The Admiralty’s orders directed him to steer to the west south-west until he arrived at the latitude at which Abel Tasman had taken his departure from Anthony Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) in 1642. This was about 41° 34’ south. From there he was to sail north, charting the entire eastern coast of New Holland. But on his approach to Tasman’s coast, severe southerly gales blew him off course, pushing Endeavour much further north than Cook intended – all the way up to 38°.

In the second week of April, 1770, Cook encountered unmistakeable signs that land was close; floating weed, a butterfly, a school of porpoises and a gannet flying north-west. In wretched Tasman Sea weather, fresh south-westerly gales and steep green seas big enough to sweep her from end-to-end, Endeavour was running under foresail and mizzen with a man in the chains sounding the depth every two hours. Endeavour had begun to enter the eastern end of what we now call Bass Strait: 150 miles wide and 240ft deep. Cook did not need anyone to tell him that the enormous waves rolling in from the west were clear pointers to the presence of a significant sea strait separating what was obviously the island of Van Diemen’s Land from what must be the southern-most part of the eastern coast of New Holland. Cook did not need to sight the strait: he was able to feel it, to read it like a book.

Land Ho! New Holland on the horizon

At daybreak on April 19, Second Lieutenant Zachary Hicks was the first to sight the mainland. Cook held his westerly course, sailing into Bass Strait for two further hours and then bearing away for the easternmost land in sight, calling the southernmost point he could then see, Point Hicks. It is now known as Cape Everard, a little west of the south-eastern extremity of Australia. Cook’s carping critics have never tired of “querulous speculation” over the conundrum – why did the great navigator not include Bass Strait on his chart? The answer may be found in Cook’s personal experience of the trouble that possession of the French islands of Miquelon and St Pierre off Newfoundland caused the British following the end of the Seven Years’ War. Cook charted those islands so he knew the geopolitical situation well.

In the treaty negotiations, the French Foreign Minister, the Duc de Choiseul, made it a precondition of peace that France must retain her fishing rights in the North Atlantic. These islands, he maintained, were essential to those rights. Although the British Prime Minister William Pitt famously declared that he would rather suffer his right hand to be cut off than allow France back into the Grand Banks fishery, he was over-ruled by his Cabinet, Choiseul got his concessions and Britain lost her sovereignty over the islands. Just as the Admiralty predicted, the French soon took advantage of the loophole to encourage smugglers and a gradual build-up of spying and naval activity, establishing in the process an uncomfortable French presence on the very doorstep of Britain’s North American colony.

Cook never stated his reasons for omitting Bass Strait from his chart of New Holland’s east coast, but as a sea officer with a clear understanding of British strategic interests in the Pacific, he certainly would not have wished to produce a document that could very well encourage enemy activity. In following the Admiralty’s instructions, he was about to claim New Holland as a purely British possession. The same principle of non-disclosure was to be applied several times as Endeavour headed north and passed potentially significant strategic objectives. This was most notably the case with Cook’s cursory description of Port Jackson.

Thus began Cook’s long-awaited running survey of the entire eastern coast of New Holland, a necessary exercise for legal possession and one that both the Dutch and the French explorers had failed to prosecute. The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty had chosen Cook wisely, knowing his dedication, his resolution and his extraordinary cartographic skills would get the job done. He was to make a chart which would remain an invaluable guide to coastal navigation for more than a century. It was a truly extraordinary feat which, even today, 250 years on, still leaves many of us in awe of the great man. Cook went where no man had ever been and any objective person must, I feel, have the greatest respect and admiration for all his extraordinary achievements.