Fishermen of Sydney Harbour

The Harbour has sustained life around it for thousands of years, from the traditional owners to the many waves of modern migrants who fished its waters; most prominent among them the Italian fishermen, writes Kevin Green.

As a new migrant myself I settled near a bay on the inner Harbour, Iron Cove, and for the last 20 years have been on its waters in various craft. An inauspicious looking bay on the edge of Sydney’s busy central business district in the Inner West of the city, yet Iron Cove has a rich history of human involvement and its waters once teemed with fish. The early hunters were the Dharug speaking Wangal people who harvested the oysters and dug crabs from the muddy mangroves surrounding the once deep and wide bay. The Cove is divided into two by a spit of rock and sand, where the Dobroyd Sailing Club now stands. On the west side of this spit are beaches, ideal for shore-based net fishing, while on the eastern side the mangroves give protection for spawning fish and crabs. The north facing mouth of the bay is crossed by the Iron Cove bridge. Its 40-foot height restricts larger yachts and at spring tides I worry as my 35-foot mast seems to just make it under with the Windex intact.

Iron Cove fleet

Inside the Cove near my swing mooring are two old squared-stern fishing boats: a light green one and a dark blue-hulled one. In my early days on the Harbour I’d sail past these boats, amazed to realise they were trawling for fish on the Inner Harbour. I’d watch as seagulls swooped after escaping prawns as the net was slowly winched in. On the blue boat I’d see a small dark-haired man darting around the deck, on his own, usually doing several jobs at once. As a former solo fisherman in the North Sea I very much related to this fellow, whose name is Francisco Illacqua. Frank, as he’s commonly known, still moors his old fishing boat near to mine. I knew his sister Gina had a clothes shop on Norton Street Leichhardt, so she made the introduction.

Back in the 1970s when the fishing was at its peak, these two trawlers were part of a 35-boat fleet based at the Cove. Other Iron Cove fishermen used Botany Bay, where according to the fascinating book The Fishermen of Iron Cove by Annette Salter, up to 20 boats lay.

Sometime later Frank and I met at Iron Cove, near where La Montage night club now sits. Before that it was the Apia Club, the hub of the Italian migrants socialising. “I retired when they closed the Harbour to fishing in 2006,” the sprightly 82-year-old told me before he leapt from my dinghy onto his boat. By 2006, the government had deemed the pollution levels to be too high for commercial harvesting of fish.

Slightly built, with a handsome face that easily breaks into a broad smile, Frank fished his whole life. From the early days as a boy in his Sicilian village of Spadafora and then 50 years on Sydney Harbour when his family migrated after WWII, when Frank was 14. Italians were part of a mass migration from their war-torn country and dominated fishing throughout the Harbour, settling at Woolloomooloo, Iron Cove and nowadays the modern Italian fleet at Sydney Fish Markets. Before them, in Iron Cove, the previous wave of migrants were the Greeks.

“Many came because, like my father, they’d been in the navy so knew Australia was a good place to settle,” explained Frank as we stood in the wheelhouse. Frank’s father had the boat built of Kauri Pine in 1954 at Berrys Bay, the same place as its green coloured sistership moored nearby. Decommissioned as a fishing boat in 2006, the nets and trawl doors were removed but most of the former trawler’s systems remain in place. A six-cylinder John Deere engine dominates the wheelhouse, attached by a belt and drive shaft to the winch in the aft cockpit. Below the starboard set steering wheel, connected by chain and shaft to the rudder, are two bunks. These bunks are filled with gear nowadays but were used on the offshore fishing trips when Frank and his father voyaged as far as Newcastle and south to Wollongong. “At Newcastle we’d run a set line to catch the sharks with flathead bait. We’d hit the big ones and throw them away but keep the little ones.”

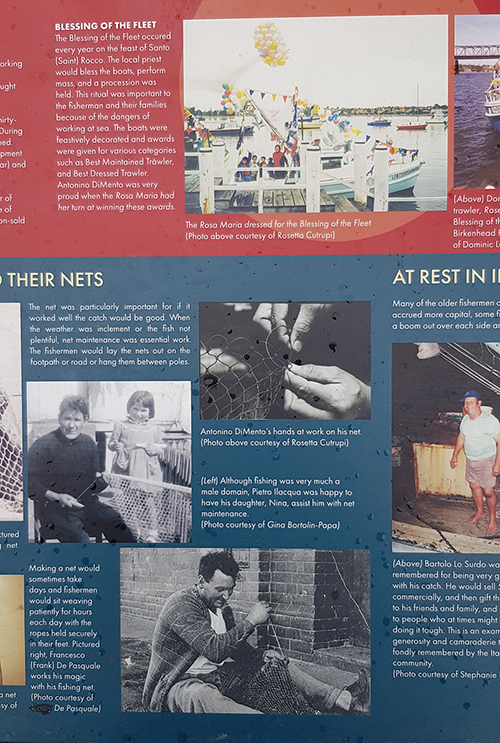

The aft cockpit has a well for live prawns and a hatch to the hold where the nets were kept. Nets were trawled by 45 fathom wire hawsers in the Inner Harbour and each trawl usually lasted for about an hour, unless Frank snagged some of the plentiful debris on the seabed. Up until the advent of nylon nets, hemp nets that became waterlogged were used.

Seasonal fishing

One of Frank’s five sisters would sometimes help mend a net, but as a male dominated profession and the only boy in the family, Frank was expected to take over from his father. “I made a reasonable living, working all summer to keep me going in the winter, and I did some house painting.” Fish migrated with the seasons, as Frank had to do for employment.

A good catch was three or four boxes of king prawns supplemented by shore-fishing for other species using a 16-foot boat. The nets would be loaded onto the smaller boat and Frank would go to various beaches to cast them. “Four men were used; one would go ashore to secure the net and the others would row in a loop to bring the other end of the net to shore with fish.” They’d catch mullet, brim, flathead and various other fish. “We used to fish the other side of the bay, on the beach at Dobroyd and on the point too.” There were also plenty of oysters around. These smaller boats were the ones originally used by the Italian fishermen, with wide transoms that held a roller mechanism for casting the nets while the men rowed in the traditional Mediterranean fashion of facing forward.

As the years passed Frank married and then had two boys to feed so there wasn’t much downtime, but when there was he enjoyed socialising in the Apia Club. Frank was never a big drinker or smoker, and his typical Mediterranean diet of olive oil, fish and vegetables clearly sustained him well over the decades; and kept his memory sharp.

Last Italian fishermen

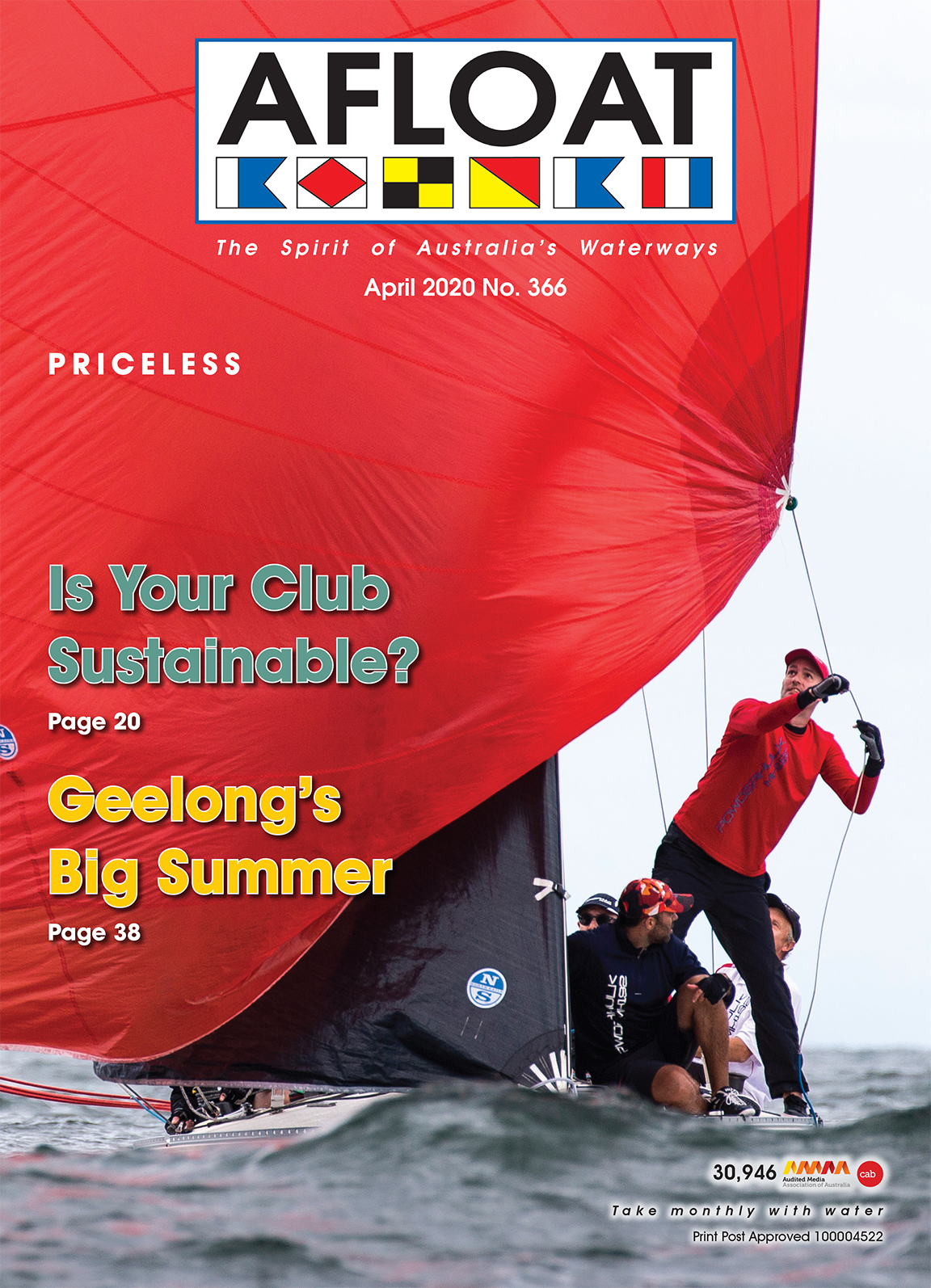

Sydney’s Fish Markets at Blackwattle Bay is where the last of the Italian fishermen ply their trade. Men like Paul Bagnato. Paul has fished for 50 years, starting at 10 when his father took him out. “I didn’t do school much, so I slept in a basket in the boat when I was little,” he laughs. The burly Italian looks like he’s hauled a few nets in by hand, but has a deckhand doing most of the manual work. His family are Calabrian, from the mainland of southern Italy, and emigrated when Paul was three. I caught up with him for a yarn during the 2020 Blessing of the Fleet at the Sydney Fish Markets. Amid the bustle of the party atmosphere with plenty shouts of Ciao! and Salve!, young and old mixed together.

Along the fishing pier, tables were laid out alongside the boats. Nowadays there are only five trawlers amid the berthed fleet. “Nearly all are Italian but there are some Aussies,” said Paul, as we sat beside his square-sterned boat Arakina, a well-kept vessel of about 35-foot.

The aft deck houses two big trawl drums and the doors for keeping the net open when fishing. “It’s about $15,000 for a net and we often snag it on the bottom.” Arakina is powered by an Isuzu diesel, the first of its kind in Australia, says Paul.

His target species is mostly whiting and flathead with several others as by-catch. His grounds are both north and south of Sydney. “We’ve had a good season this year and we’re doing well.

“I owned my first boat when I was 17-years-old, and I’ve had a good life on the sea.” His only complaint is the public’s attitude to his industry. “People should appreciate not just our catch but the fishermen themselves.”

As a former commercial fisherman, I echo Paul’s sentiments. I’d love to take some of these people out to sea, to show them how working on boats like this can be dangerous. Dangers include the many moving parts in the confines of a small boat, such as the wire hawsers, the large trawl doors and the winch drums that can easily snap a limb. Add to this scenario a heavy swell and it becomes a very dangerous place for the unwary, or even experienced hands that have a careless moment.

But these Italians have the sea in their blood and men like Paul intend to continue the tradition.