Dr Ted from Berkley

Back in 2011, after we lost ’arry Driftwood, we asked Quirky if he could come up with a Christmas article for our December 2011 issue. He did. Then we asked if he had any more. He had just published the book Foul Bottoms with 27 stories but thought he might have two or three more … this is his 100th article for Afloat.

Back in 2011, after we lost ’arry Driftwood, we asked Quirky if he could come up with a Christmas article for our December 2011 issue. He did. Then we asked if he had any more. He had just published the book Foul Bottoms with 27 stories but thought he might have two or three more … this is his 100th article for Afloat.

You have heard me rattle on about the Berkley ship canal before. As a kid, staying at my grandfather’s fishing shack on the banks of the Severn, I watched the river flowing down towards Gloucester and on to the rest of the world. It took 34 years to gouge the canal out of 19 miles of mud and muck using private enterprise and shovels. Let’s have a look at the local doctor, Dr Ted, a country physician at the time of its building who changed the face of the world.

The history enthusiasts among you will recall Berkley Castle which gained an unsavoury reputation for the imaginative but particularly gruesome execution of King Edward 2nd in 1327. The canal was started in 1793 to bypass the most treacherous stretch of the Severn estuary so ships would have an easier passage to Gloucester. The idea was to develop Gloucester as a port for the Severn and Avon River and canal links to England’s heart lands. Still a delightful way to see the country. The canal was funded mainly by local merchant to promote this. It ran out of money with only 5½ miles being built in 1799. However, in 1817 the introduction of the Poor Employment Act was a Jobseeker program to deal with the mass unemployment at the end of the Napoleonic Wars which brought government funds in to complete the project in ten years. Their swing bridges are manned from delightful Palladian cottages which house the keepers. It still amazes me to watch the 40-foot tides of the estuary flowing at up to 8 knots around the structures of the outer sea lock. How was all this was built 250 years ago in the swirling silt without the use of sheet metal piling?

No doubt the local doctor would have been interested in watching the construction taking place. Doctor Ted was a man of science. He built hot air balloons and made successful assents and an even more successful crash landing. It is said that on one of his flights he wound up ploughing the petunias of Kingscote Park Gloucestershire much to the annoyance of its owner Robert Kingscote but to the delight of his daughter Catherine (see main illustration). We can assume that Robert forgave the aerially intruding doctor. He had an unwed daughter on his hands who was heading for her thirties. An unmarketable commodity in those days. In 1788 he happily gave her away in marriage to the 39-year-old Dr Ted.

While he was at school, the 8-year-old Ted was treated with variolation against smallpox. This was a process of collecting scabs from smallpox victims with only a mild case and left to dry. They were then rubbed into scratches made on the skin of the patient. It was a method developed in China and the Middle East so patients were infected with a mild dose of smallpox. The Chinese blew powdered smallpox scabs up patient’s noses. After about four weeks the symptoms would subside and the patient would then be immune to further infection.

A 14-year-old Ted was apprenticed to a doctor in the charming village of Chipping Sodbury in the Cotswolds and at 21 was trained at St Georges Hospital Medical School in London before returning to the country life of his beloved Gloucestershire 22 years later.

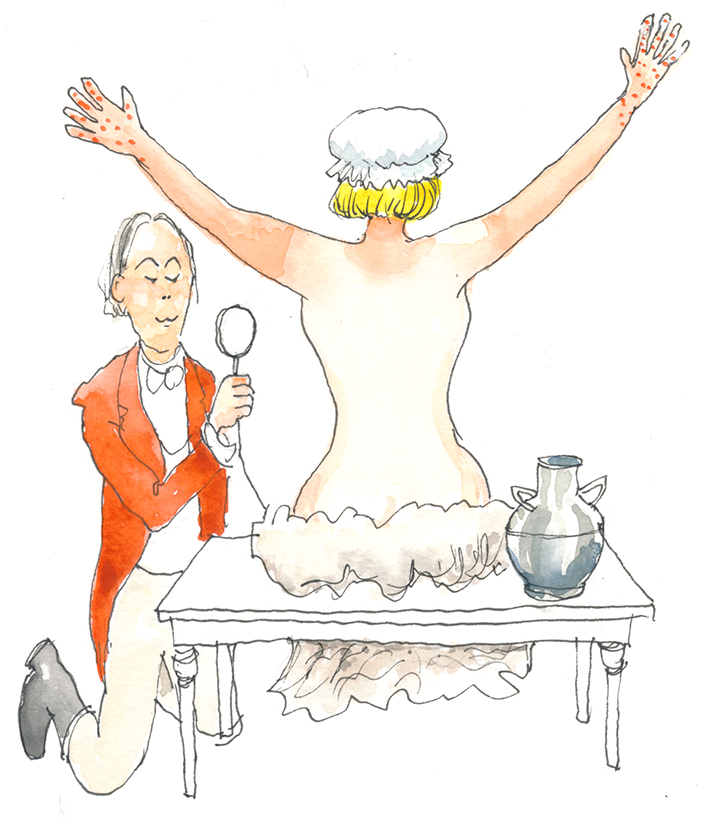

Voltaire wrote at this time that 60% of the population caught smallpox and 20% died from it. In 1768 it was discovered by the research of Dr John Fewster that a person who had suffered cowpox would not contract the more deadly smallpox. The two ailments were related but cowpox was rarely fatal. The dashing Dr Ted kept his eye on the local milkmaid population and noticed that although their hands often became infected with cowpox blisters from constantly pulling udders, the rest of them had clear complexions unravaged by smallpox and seemed to be immune from it.

In 1796, Dr Ted tried an experiment that would change the world. Milkmaid Sarah Nelmes had contracted cowpox from a cow named Blossom. He scraped some of the scabs from her hands into scratches he made in both arms of 8-year-old James Phipps, the son of his gardener. The same age as Dr Ted was when he was variolated. This produced a mild fever and uneasiness in James, but not a full-blown infection. He later gave the family a cottage.

It sounds risky to us now, but cowpox was not fatal unless you had a dodgy immune system. Dr. Ted later treated his own 11-month-old son Robert and 22 other patients, all of whom became immune from further infections of smallpox. He named this system after its bovine source: vaccination from the Latin for cow, vacca.

Ergo: Immune from cowpox = immune from smallpox.

Some of the medical profession at the time were as receptive to medical science as the White House is today and the Establishment was reluctant to acknowledge this breakthrough in medical science. But Dr Ted had one fervent admirer whose support finally brought him the recognition he so richly deserved.

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon had all his troops vaccinated and although he was at war with Britain at the time. He allowed a prisoner exchange requested by Dr Ted saying, “I could not refuse anything to one of the greatest benefactors of mankind.” There, put that in your CV and show it to the doubters. His strenuous work on vaccination meant he had to give up his GP practice in Berkley. A number of supporters, including the King petitioned Parliament to grant him £10,000 to continue his research. The Royal College of physicians followed in 1807 and finally accepted his work and he was awarded, at the height of the Napoleonic wars the equivalent of a third of a battleship. He received an astonishing £20,000 to continue his research. (HMS Victory had cost £63,176 and three shillings.) That would get you a lot of cows. And milkmaids. All this cash, but strangely, no knighthood. He received walls full of international recognition and awards including being made Physician Extraordinary to George lV. The one that gave him the greatest satisfaction was the recognition of his home village; he was made Mayor of Berkley.

Vaccination was expanded to give immunity to dozens of other diseases and it is reckoned Dr Ted saved over 530 million lives. The WHO tells us that smallpox was eradicated from the face of the earth on December 9th December 1979.

The last agonising death from smallpox was in 1978. You probably think that this happened in some reeking insanitary village in the armpit of a third world dump.

Close.

It was in my hometown of Birmingham. Janet Parker was a 40-year-old medical photographer at Birmingham Medical School where they had a smallpox laboratory. It was never established how Janet contracted the fatal disease but Professor Bedson, the man in charge went into his garden shed and left a bloody mess for his poor wife to find. Janet’s father died from cardiac arrest at hearing of the death of his daughter. Her mother contracted a mild case of smallpox herself and missed both the funerals of her daughter and husband.

There are labs in the USA and Russia which hold samples under very tight security, we are told, in case further research becomes necessary. I hope they have better security than they did in Birmingham. They couldn’t control it then and that was before Al-Qaeda and friends set up shop in the High Street.

Unfortunately Dr Ted lost his wife and 21-year-old son to another great killer of the age which could not be helped by his vaccinations. Despite living on the Severn estuary which channeled mild temperate sea air up to the Vale of Evesham to create the fruit bowl of England, they both succumbed to TB, or consumption as it was then known. He did not live to see the opening of the canal that ran close by his grand house. He died in 1823 aged 73 and James Phipps attended his funeral.

His legacy lives on the creation of the British Vaccination Acts, which banned variolation and in 1853 went on to make vaccination free and compulsory to all children within three or four months of birth. Variolation did not come with a lifetime guarantee and some patients developed small pox after they had been treated. But still there were those who would deny their children this life saving treatment. I found out in later life that my mother did not have me nor my sister vaccinated against diphtheria nor polio, two killers in the forties and fifties, because as a child, she heard of someone who died as a result of a vaccination.

But the legacy of Dr Ted, the local doctor of Berkley, known to a grateful world as Dr Edward Jenner, lives on and the whole world is in his debt. We all hope that somewhere out there, someone will follow his path in producing a treatment for COVID-19.

And there is another member of the research team that is still remembered. Blossom, the cow. Her hide hangs in grateful recognition in the library at the St Georges Hospital Medical School, the Alma Mater of Dr Edward Jenner.